Overall, disruptions to EBIs were comparatively minimal, and Rwanda's health system bounced back quickly.

A critical theme that emerged from interviews with KIs and other data is that Rwanda was able to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and prevent and mitigate its impact on EBIs because the country had already built a resilient health system to respond to the everyday health needs of its population. Consequently, it could quickly develop and implement a set of strategies designed specifically to stop the spread of the novel coronavirus and maintain EBI delivery in this pandemic context. Second, and more important, Rwanda could continue to implement and adapt the same strategies it was already using to maintain key health services—especially those aimed at boosting MCH. Together, these strategies enabled Rwanda to reverse initial EBI disruptions and keep delivering key services throughout the COVID-19 emergency.

COVID-19 response in Rwanda

Rwanda’s effective response to COVID-19 mitigated the impact of the pandemic and helped the country maintain EBI delivery by preventing the health care system from being overwhelmed by a surge in COVID-19 infections. For instance, officials provided CHWs and health facilities with PPE and other essential supplies so that they could safely continue to deliver evidence-based interventions. A toll-free telephone line provided accurate information about the novel coronavirus, reducing community fear and encouraging people to seek health care when they needed it. Finally, officials established command posts from the national level (the National Joint Task Force) to the cell level. These posts coordinated logistics, daily information-sharing, and community engagement to reduce barriers to COVID-19 prevention and treatment and enable the continued provision of EBIs.

The resilient health system Rwanda built prior to the COVID-19 emergency enabled the country to implement these responses to the pandemic itself. That system also gave officials and health care providers a battery of pre-existing strategies they could adapt (where necessary) to maintain EBI delivery and mitigate drops in coverage of EBIs, even when it was under unusual strain.

Most of the strategies Rwanda implemented to prevent or respond to COVID-related drops in EBIs coverage predated COVID-19 and were adapted to suit their new context, but a handful were new. All these interventions fall into three main categories: human resources for health, infrastructure, policy, and leadership.

Disruptions by district

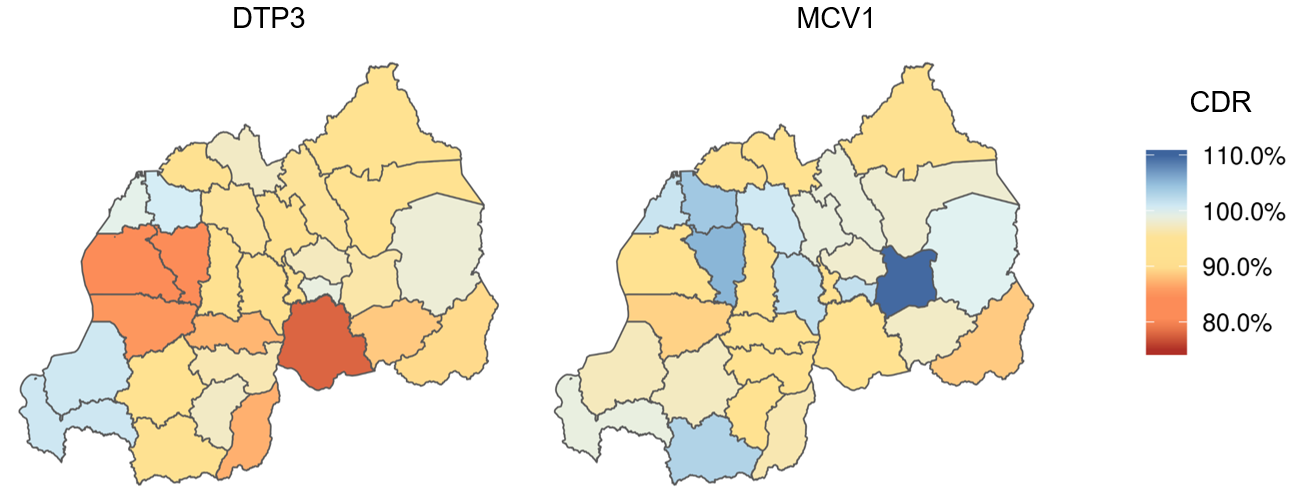

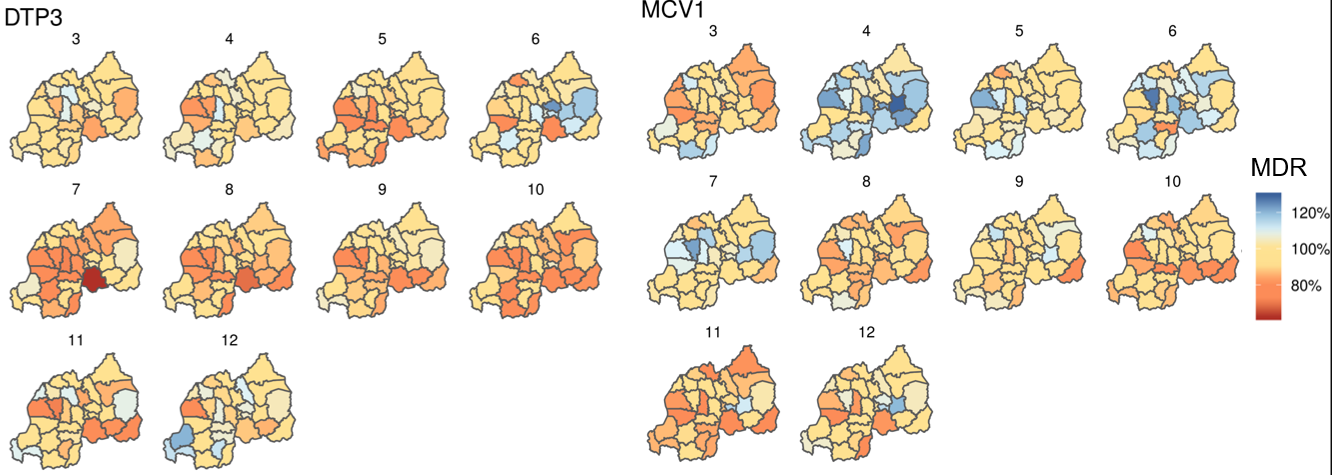

In partnership with the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, we conducted an analysis of the disruption ratio of key EBIs. The monthly disruption ratio compares the coverage for a given month in 2020 to that same month in 2019, normalized by changes for that month relative to January and February of that year to account for seasonality. In addition, we calculated the cumulative disruption ratio over the full year, comparing the total disruptions from March to a given month in the year, and also normalized by comparing this to the same time period in 2019.

The heat maps below show both the monthly disruption ratios and cumulative disruption ratios over time, for DTP3 and measles first dose (MCV1). Disruptions were generally minimal in most districts, and recovery generally occurred within a few months. Ratios above 100 percent indicate that coverage was higher in 2020 than in the comparable month in 2019, indicating either variability or catch-up campaigns or both. This is especially significant when the ratio changed drastically from one month to the next (for instance, from March to April with the first dose of the measles immunization).

Monthly Disruption Ratio of Evidence-based Interventions in Rwanda, March to December 2020

Cumulative Disruption Ratio of Evidence-based Interventions in Rwanda, 2020